Scroll to:

Circulating MicroRNAs Are Promising Biomarkers for Assessing the Risk of Antipsychotic-Induced Metabolic Syndrome (Review): Part 2

https://doi.org/10.30895/2312-7821-2025-499

Abstract

INTRODUCTION. The first part of this article discussed antipsychotic-induced metabolic syndrome (AIMetS) as a common adverse reaction to the pharmacotherapy of psychiatric and addiction disorders. The authors presented a review of basic and additional clinical and biochemical biomarkers of metabolic syndrome (MetS) in general and AIMetS in particular in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and outlined approaches to measuring these biomarkers. Detecting changes in the expression of circulating microRNAs in the blood can be considered a promising method for predicting and diagnosing AIMetS.

AIM. This study aimed to evaluate the role of circulating microRNAs as epigenetic biomarkers of the key components of AIMetS pathogenesis.

DISCUSSION. The authors reviewed and collated the results of academic and clinical research (2012–2024) with a focus on the role of circulating microRNAs involved in the key AIMetS pathogenesis and progression pathways. The authors analysed the results of studies on the role of circulating microRNAs in the blood as regulators of the key components of MetS and AIMetS pathogenesis. The studied components of pathogenesis included oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, adipogenesis regulation (and abdominal adiposity development), lipid metabolism, high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol homeostasis, atherogenesis, and hepatic steatosis, as well as the regulation of insulin and leptin sensitivity, glucose metabolism and appetite, and insulin, neuropeptide Y, orexin, thyroid and parathyroid hormone expression. A personalised assessment of the safety of pharmacotherapy may depend on the pattern of circulating microRNAs that induce or inhibit the main components of AIMetS pathogenesis. The differences in the results of the reviewed microRNA studies may be due to the differences in the design of these academic (mainly) and clinical studies and their lack of consideration for modifiable and unmodifiable risk factors for developing AIMetS. The authors proposed a microRNA classification according to the risk level of developing AIMetS.

CONCLUSIONS. The findings demonstrate that the sensitivity and specificity of epigenetic biomarkers of AIMetS can vary widely, depending on the nature of their influence (predictive or protective) on one or several pathogenetic components of this widespread adverse reaction to psychopharmacotherapy. The most studied microRNAs are predictive biomarkers of oxidative stress (miR-1, miR-21, miR-23b, miR-27a, etc.) and systemic inflammation (miR-21, miR-23a, miR-27a, etc.) in patients at high risk of developing MetS and AIMetS. Promising epigenetic AIMetS biomarkers include microRNAs that affect the expression of and sensitivity to neuropeptides, including neuropeptide Y (miR-let7b, miR-29b, miR-33, etc.), leptin (miR-let7a, miR-9, miR-30e, etc.), and orexin (miR-137, miR-637, miR-654, etc.).

Keywords

For citations:

Shnayder N.A., Nasyrova R.F., Pekarets N.A., Grechkina V.V., Petrova M.M. Circulating MicroRNAs Are Promising Biomarkers for Assessing the Risk of Antipsychotic-Induced Metabolic Syndrome (Review): Part 2. Safety and Risk of Pharmacotherapy. 2025;13(4):394-410. https://doi.org/10.30895/2312-7821-2025-499

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSDs) are common socially significant mental disorders associated with a reduced life expectancy [1][2]. Over the recent years, the role of antipsychotic-induced metabolic syndrome (AIMetS) in SSD patients has proven to be one of the main death causes in these patients [3]. Improving the pharmacotherapeutic safety of antipsychotics (APs) and assessing the risk of AIMetS and associated cardiovascular diseases is one of priorities for managing SSD patients [4]; this also implies finding and implementing new AIMetS laboratory biomarkers in real clinical practice [5].

Small non-coding ribonucleic acids (microRNAs) play an essential role in the regulation of various pathophysiological processes underlying AIMetS progression in SSD patients. The key links of these AIMetS pathogenic pathways include oxidative stress [6][7]; systemic inflammation [8, 9]; adipocyte differentiation and abdominal obesity [8][10][11]; lipid and glucose metabolism [8][11–23]; appetite control [24–28]; neuropeptide Y (NPY) level [24][29][30]; leptin sensitivity [9][28][30]; levels of orexin [31][32], testosterone [33], thyroid [34] and parathyroid [35] hormones.

In the first part of this review [36], it was shown that detected changes of circulating microRNA expression levels in the available samples (blood, saliva, urine, etc.) as epigenetic AIMetS biomarkers is a promising alternative method for prediction and diagnosis of the discussed adverse reaction in SSD patients as compared to genetic biomarkers (DNA samples). Circulating microRNAs demonstrate stability at sample storage (including multiple freezing and thawing cycles), reproducibility, and consistent signatures in individual patients [36].

Predictive microRNAs associated with an increased risk of the main AIMetS pathogenic components in SSD patients deserve a more detailed consideration in order to understand the mechanism of metabolic changes.

The aim of the study was to evaluate the role of circulating microRNAs as epigenetic biomarkers of the key components of AIMetS pathogenesis.

The literature search methods were described in the first part of the review [36].

MAIN PART

MicroRNAs as epigenetic biomarkers of the main AIMetS pathogenic components

Oxidative stress

Numerous clinical and experimental reports demonstrate changes in the oxidant / antioxidant balance of SSD patients induced by APs [37–40]. First-generation APs (haloperidol) and second-generation APs (clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone) significantly reduce superoxide dismutase and catalase activity, activate lipid peroxidation and buildup of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [38]. The signaling pathway of endogenous nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a part of protection mechanism against oxidative stress that plays an essential role in both SSDs and AIMetS; however, complex balance of Nrf2 with NF-kB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) and its crosstalk with the Nrf2 transcription factor is crucial for severe oxidative stress in SSD patients [39].

The microRNAs inducing oxidative stress include miR-1, miR-21, miR-23b, miR-27a, miR-28, miR-29, miR-34a, miR-92a, miR-93, miR-101, miR-106b, miR-128, miR-129-3p, miR-140, miR-142, miR-144, miR-146, miR-148, miR-153, miR-155, miR-181c, miR-193b, miR-320, miR-365, miR-375, miR-383, miR-495, miR-503, and miR-802. The mechanisms causing oxidative stress are related to the Nrf2 signaling pathway and maintain a high control over this pathway at its different stages. NFE2L2/Nrf2 is a critical biomarker associated with cytoprotective reactions in response to oxidative and electrophilic stresses. The kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) ubiquitinates Nrf2 and directs it to degradation, while the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway is the most important cytoprotective pathway responding to increased ROS levels [41]. MicroRNAs are involved in the control of Nrf2 signaling pathway through several mechanisms: altering Nrf2 nuclear translocation; effecting Nrf2 expression; controlling mediators located upstream of Nrf2; and modulating Keap1.

Sirtuin 1 (Sirt1) is a NAD+-dependent deacetylase, an important antioxidant enzyme associated with diabetes mellitus. Sirt1 uses the first pathway, PGC1a/ERRa, to induce Nrf2, although it can also directly activate Nrf2 using other mechanisms. For example, patients with olanzapine-induced MetS had markedly lower Sirt1 plasma levels than schizophrenia patients without MetS and healthy controls [40]. Much less studied is sirtuin 3 (Sirt3) [42] that positively regulates the expression of O1 and O3 transcription factors (forkhead box protein, FOXO1/3), causing an antioxidant response [7]. Sirt3 is expressed in tissues and organs with a high metabolic rate, including liver, brain, heart, and brown adipose tissue, and plays an important role in the regulation of oxidative stress and mitochondrial metabolism [43]; therefore, the effect of microRNAs on Sirt3 expression is of certain scientific and clinical interest.

Thus, miR-23b induces oxidative stress through decreased Sirt1 and Nrf2 expression [7][44]. MiR-34a overexpression downregulates the gene encoding Nrf2, with a marked decrease in mRNA and Nrf2 protein. At the same time, when miR-34a expression is inhibited, the Nrf2-dependent antioxidant pathway is restored [6][45]. MiR-92a inhibits Sirt1 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) [46] while activating inflammasomes, which aggravates endothelial dysfunction under oxidative stress [7]. MiR-128 reduces Sirt1 expression level and the expression levels of the Nrf2 protein, thus contributing to oxidative stress [6][7]. MiR-140 directly affects Nrf2 and Sirt2 levels, changing expression levels of HO-1, NQO1, Gst, GCLM, Keap1, and FOXO3a [6].

MiR-27a, miR-142, miR-144, and miR-153 are regulatory microRNAs for Nrf2 that reduce its transcription [6]. Activation and expression of the Nrf2 signaling pathway and its downstream mediator HO-1 are visibly accelerated when miR-320 expression is inhibited [6]. MiR-383 mediates oxidative stress and apoptosis by suppressing type 3 peroxiredoxin (PRDX3) [7].

Systemic inflammation

Typical and atypical APs are known to affect the production of proinflammatory cytokines [47]. For example, haloperidol can alter the levels of interferon gamma (IF-γ), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL-2, IL-10, IL-237), etc., while clozapine, risperidone, and quetiapine (in addition to the above cytokines) also alter the production of IL-4, IL-104, and IL-646 [48]. Studies evaluating the correlation between AP intake and changes in systemic inflammatory biomarkers plausibly demonstrate the change in these blood biomarkers; however, their level and impact on the course of psychiatric disorders and the AIMetS risk are still a subject of discussion [49][50].

Systemic inflammation is marked by increased serum levels of acute-phase proteins and proinflammatory cytokines, including C-reactive protein, TNF-α, IL-1b, IL-6, and IL-17, as well as infiltration of macrophages and T-lymphocytes in insulin-dependent tissues [8]. In general, microRNAs regulate various inflammation stages, starting with initiation, alteration, exudation, proliferation, and resolution, through both positive and negative feedback. In case of a positive feedback, a series of events limits not only the pathogen invasion, but also the successful restoration of damaged tissues. On the contrary, negative feedback activated by severe inflammation helps maintain tissue homeostasis.

Over the recent years, microRNAs (miR-21, miR-23a, miR-27a, miR-29a, miR-34a, miR-34c, miR-92a, miR-132, miR-138, miR-155, miR-200, and miR-let7a) have been identified that are capable of mediating systemic inflammation through their altered expression in certain immune cells. As part of the inflammatory response, microRNA expression is often regulated at various stages, including synthesis, processing, and stabilisation of pre- or mature microRNAs [8][9].

Elevated miR-let7a levels were found to activate the NF-κB proinflammatory pathway by targeting the nuclear factor inhibitor κB (IκB) kinase. Elevated miR-21 levels in adipose tissues are typical for people with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus; in fact, this is the leading clinical MetS manifestation associated with sluggish systemic inflammation and increased adipogenic differentiation through modulated signaling of transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-β1). MiR-21 also plays a crucial role in angiogenesis through VEGFA regulation [9][51][52].

The pro-inflammatory miR-23a mechanism is associated with the activated pro-inflammatory NF-κB pathway in M1 macrophages and parallel inhibition of the anti-inflammatory JAK1/STAT6 pathway [9][53]. Deficiency of Sirt1 antioxidant induces miR-132 overexpression in human primary preadipocytes, thus inducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The miR-34 family (miR-34a and miR-34c) induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines by targeting G protein (LGR4); it delays the local inflammatory response [9][54].

Overexpression of proinflammatory miR-92a leads to increased regulation of several genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines in the recipient macrophages [9]; overexpression of miR-138 and miR-155 promotes systemic inflammation by activating NF-κB proinflammatory signaling pathway, as well as MyD88 and TRIF pathways that contribute to increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines and suppression of Sirt1 cytoprotective protein [9][55].

MiR-200 demonstrates a pro-inflammatory response by effecting the synthesis of Zeb-1 protein involved in increasing the activity of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) enzyme and monocytic chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) in vascular smooth muscle cells with type 2 diabetes mellitus [9]. This pathway is also significant for MetS mechanism in patients with psychiatric disorders receiving APs [56].

Adipogenesis regulation and mechanism of abdominal obesity

Adipogenesis is the process that allows adipocytes to develop from adipose-derived stem cells and form fat tissue [57]. Impaired adipogenesis and regulation of adipose tissue metabolism are associated with various AIMetS manifestations (obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular diseases). Understanding the mechanism, functions, and composition of the adipocyte secretome is critical for developing targeted MetS and AIMetS therapy in SSD patients [58]. First-line APs (haloperidol, etc.) and newer generations (olanzapine, clozapine, risperidone, etc.) can induce adipogenesis accompanied by underexpression of proteins binding sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1) and 2 (SREBP2), fatty acid synthases (FAS), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGR), and PPARG gene encoding the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma [59]. In addition, clozapine and olanzapine enhances differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes into mature adipocytes via activated SREBP1 pathway [60].

MicroRNAs can directly regulate adipogenesis. Studies have established an inducing effect on adipogenesis and the development of abdominal obesity for a number of microRNAs (miR-17, miR-20a, miR-21, miR-103, miR-128-1, miR-143, miR-144, miR-146b, miR-148a, miR-194, miR-210, miR-322, miR-375, and intronic miR-378). One of the regulation mechanisms of microRNA-mediated adipogenesis is regulating the expression of transforming growth factor-β (TGF—β), a protein that regulates adipocyte proliferation, differentiation, and growth and modulates the expression and activation of other growth factors, including IF-γ and TNF-α [58].

Thus, miR-21 stimulates adipogenesis by modulating the signal transduction of TGF-β1 preadipocytes. Increased adipogenic differentiation in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes is associated with increased expression of miR-17, miR-21a, miR-21, and miR-143, which stimulate the expression of adipogenic transcription factor C/EBPα and enhance TGF-β signaling [8][10].

MiR-103 doubles the expression of adipogenic transcription factor PPARγ alongside with increasing the expression of fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) and adiponectin by about 9 and 4 times, respectively [10]. MiR-128-1 also regulates the homeostasis of circulating lipoproteins, as well as the expression of genes encoding PPAR and other regulators of fatty acid oxidation and systemic inflammation, leading to abdominal obesity [11].

MiR-144 downregulates the expression of FOXO1 transcription factor by suppressing adiponectin stimulation, and therefore reduces the inhibiting effect of adiponectin on adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes; miR-146b promotes adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes by suppressing Sirt1 expression [10].

A group of microRNAs, such as miR-148a, miR-194, miR-210, and miR-322, induces adipogenesis by suppressing signaling of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, a key inhibitor of adipogenesis [10][61].

MiR-375 overexpression initiates adipocyte differentiation by increasing C/EBPα and PPARγ, simultaneously inducing FABP4 adipocytes and accumulating triglycerides. MiR-375 overexpression promotes adipogenesis through differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and suppression of signal-regulated extracellular protein kinase (ERK1/2) phosphorylation [10].

Regulation of lipid metabolism

Various mechanisms underlying lipid metabolism dysregulation caused by taking APs of different generations continue to be actively studied (including AP-induced hypercholesterolemia and increased atherosclerosis risk in SSD patients, among them adults and adolescents) [62][63]. Thus, Delacrétaz et al. [64] demonstrated that 49% of SSD adolescents experienced an early increase in total cholesterol levels by 5% or more during the first month of taking APs, while 33% developed hypercholesterolemia during the first year of treatment. In patients with high-density lipoproteins (HDL) decreased by ≥5% from baseline during the first month of AP intake; this biomarker decreased more significantly after 3 months of treatment compared to patients whose level dropped by less than 5%.

MicroRNAs are known to have a direct effect on lipid metabolism by inhibiting lipid metabolism of miR-30c, miR-33a, miR-33b, miR-34a, miR-128-1, miR-144, miR-148a, miR-223, and miR-246b.

MiR-34a mediates hepatic response to metabolic stress associated with lipid overload by downregulating the expression of hepatocyte nuclear transcription factor 4A (HNF4A), which is a critical transcription factor in lipid metabolism. Another regulatory centre that suppresses genes involved in cholesterol synthesis is miR-223. In addition, miR-223 inhibits the expression of the SR-BI scavenger receptor by hepatocytes that transports cholesterol from HDL to the liver. The final result of miR-223 effect is a decreased cholesterol level in the liver [11].

MiR-246b affects the mRNA of the thyroid hormone beta-receptor (Trβ) in the liver, causing changes in the expression of genes responsible for lipid metabolism and a decrease in intracellular lipids [34].

The mechanisms of miR-30c, miR-33a, miR-33b, miR-128-1, miR-144, and miR-148a will be described below, since their pivotal point is the regulation of LDL and HDL cholesterol homeostasis [11–15].

Regulation of HDL cholesterol homeostasis

The intake of first- and new-generation APs disrupts HDL homeostasis and leads to their decrease in serum [65]. In a population-based study with the participation of 3,255 patients, Richards-Belle et al. (2023) showed that the use of APs was strongly associated with lower serum HDL levels and higher triglyceride levels [66].

Over the recent years, it was established that miR-33a and miR-33b co-ordinate inhibition of the reverse cholesterol transport from the periphery back to the liver by suppressing ATP-binding cassette transporters A1 (ABCA1), and inhibit cholesterol excretion from the body by suppressing ABCB11 protein transporter and lipid-transporting ATPase 8B1 (ATP8B1) that provide cholesterol elimination from the liver into the bile. They also inhibit fatty acid oxidation enzymes, which leads to a decrease in lipid metabolism in cells [11]. The effects of miR-128-1, miR-144, and miR-148a are associated with suppression of ABCA1 expression. The combined effect of these microRNAs is to reduce cholesterol outflow into HDL [13][14], which makes them promising epigenetic biomarkers of AP-induced dyslipidemia.

Regulation of LDL cholesterol homeostasis

MicroRNAs associated with decreased HDL levels (miR-128-1, miR-148a) contribute to an increase in LDL levels by inhibiting the expression of their receptors that allow peripheral cells to absorb lipids from circulating LDL. Thus, inhibition of miR-128-1 and miR-148a in mice led to increased expression of LDL receptors and increased the clearance of circulating LDL, which subsequently led to their decreased plasma levels [13].

Atherogenesis regulation

Atherogenesis is an important link in MetS and AIMetS pathogenesis. It was shown that long-term use of some atypical APs may increase the risk of atherosclerosis and associated cardiovascular diseases in SSD patients [67]. In recent years, it has been demonstrated that, in addition to the previously described influence on lipid metabolism and adipogenesis, microRNAs regulate atherogenic processes. Thus, miR-33 inhibition increases cholesterol transport from macrophages to plasma, liver, and faeces by more than 80%, which can prevent atherosclerosis and formation of foam cells by increasing ABCA1 activity and, as a result, increasing HDL levels. MiR-33 overexpression is also related with other atheroprotective effects, including regulated functional polarisation of macrophages [11].

MiR-144 is another strong inhibitor of cholesterol outflow from various tissues, including macrophages. It has been shown that miR-144 overexpression in animal models slowed down atherosclerosis progression [14].

Hepatic steatosis

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease globally and one of the many manifestations of insulin resistance and MetS [68]. It is a progressive disease described as insulin resistance and inflammation associated with the fat accumulation in the liver. Regardless of the clinical diagnosis, NAFLD incidence is higher in patients taking APs than in the general population [68]. Overexpression of miR-34a (in both humans and mice) induces NAFLD. Inhibition of this microRNA in a murine model had a therapeutic effect in NAFLD associated with miR-34a-mediated repression of PPARα and subsequent suppression of fatty acid metabolism in the liver [11].

Regulation of insulin sensitivity

Long-term use of APs exerts a well-known negative effect on insulin receptors and various insulin signaling pathways. Consequently, the risk of insulin resistance as one of the leading links in AIMetS pathogenesis increases in SSD patients [69-71]. A number of microRNAs such as miR-let7, miR-15b, miR-19, miR-29, miR-33a/b, miR-103, miR-107, miR-143, miR-155, miR-223, miR-378, miR-451-1, and miR-802 reduce insulin sensitivity in various organs and tissues.

Highly conservative miR-let7 is expressed in the skeletal muscles, where it inhibits insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2) and insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 (IGF1), thereby reducing muscle tissue sensitivity to insulin [11].

MiR-15b overexpression blocks IRS1 insulin receptors in hepatocytes, thus causing hepatic insulin resistance [11]. MiR-19 inhibits phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) involved in insulin signaling in the liver [11][72]. MiR-33 family blocks the IRS2 substrate, a key component of the insulin signaling pathway [11]. In adipocytes, miR-103 and miR-107 suppresses caveolin expression; this weakens the signals transmitted to insulin receptors [16].

Overexpression of miR-143 causes insulin resistance due to inhibited ORP8 (OSBP-related protein 8), a member of oxysterol-binding protein (OSBP) family, and blocked PI3K/AKT pathway activation by insulin [11][73]. Circulating miR-155 secreted by macrophages inhibits insulin signaling by suppressing PPARγ expression in myocytes (skeletal and heart muscles) and hepatocytes [11][74].

IRS1 (insulin receptor substrate 1) and SLC2A4 genes (solute carrier family 2, member 4; also known as GLUT4 — glucose transporter gene type 4) involved in the regulation of glucose metabolism are targeted by miR-223. This microRNA also modulates the expression of insulin-regulated transporter protein GLUT4. Dysregulated expression of this microRNA can downregulate the insulin signaling cascade, potentially causing insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus [8].

MiR-378 inhibits the expression of the catalytic subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) p110a. Since PI3K is a key transducer of insulin signaling, sustained overexpression of miR-378 leads to insulin resistance [17], while miR-802 affects the expression of HNF1B transcription factor by enhancing the regulation of HNF1B-associated SOCS1 and SOCS3 genes (encoding type 1 and 3 suppressors of the cytokine signaling pathway), which impairs insulin signaling by inhibiting phosphorylation IRS proteins [18].

Regulating insulin expression

APs can block muscarinic M3 receptors on the membrane of beta cells in the pancreatic islets of Langerhans, leading to suppressed insulin secretion stimulated by cholinergic receptors, and prevents glucose transport to peripheral tissues. It is believed that the defective β-cell function caused by prolonged use of APs results from a combination of insulin resistance and decreased insulin secretion stimulated by glucose [75]. Insulin expression, as well as fusion and release of insulin granules, is regulated by microRNAs.

The microRNAs that inhibit insulin expression and secretion are miR-7a, miR-26a, miR-29, miR-124a, miR-130a, miR-130b, miR-152, miR-187, miR-200, miR-204, miR-375, and miR-802.

MiR-7a inhibits transcription of the insulin gene by downregulating the expression of paired box protein Pax6 (Pax-6 paired box protein, also known as aniridia type II protein (AN2) — type II aniridia protein or oculorombin); moreover, it inhibits transcription of the gene encoding insulin-like peptide Ilp2 by an unknown mechanism. In addition to regulating insulin expression, miR-7a reduces the amount of insulin released by beta cells of the pancreatic islets of Langerhans by suppressing proteins involved in cytoskeletal reorganisation. This microRNA inhibits the expression of CAPZA1 (capping protein (actin filament) muscle Z-line, alpha 1) gene encoding alpha-1 subunit of the protein covering F-actin, needed for releasing insulin-like peptides and increasing their blood levels. The proteins encoded by these genes bind to the pointed ends of F-actin and prevent polymeriыation / depolymerisation of actin filaments, thus inhibiting the active growth of actin filaments and stabilising the cytoskeleton. Overexpression of this microRNA inhibits production of α-synuclein, which acts as a molecular chaperone during the assembly of protein complexes associated with synaptosomes (SNARE complexes). In turn, α-synuclein and SNARE fuse intracellular transport vesicles with the target membrane, limiting SNARE-dependent assembly of insulin and fusion of insulin granules [11].

MiR-26a is expressed in beta cells of the pancreatic islets of Langerhans and inhibits expression of the voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel subunit alpha-1C that mediates calcium influx and the SNARE-dependent fusion of insulin granules with the plasma membrane of beta cells, with the subsequent release of insulin into the bloodstream [19].

Synthesis of monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) in the beta cells can be inhibited by overexpression of three miR-29 paralogues that directly suppress the matrix RNA of MCT1 gene. This transporter protein transfers lactate and pyruvate to the mitochondria. When MCT1 production is inhibited, beta cells stop producing insulin during exercise, which leads to a significant increase in the circulating lactate and pyruvate [11].

MiR-130a, miR-130b, and miR-152 reduce the levels of glucokinase (GCK) and the E1-α1 subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDHA1). GCK is active at the first stage of glycolysis. PDHA1 converts pyruvate derived from glycolysis into mitochondrial acetyl-CoA. Overexpression of these microRNAs reduces the intracellular ATP:ADP ratio, insulin synthesis and secretion [20].

Experimental overexpression of miR-187 in an animal model led to inhibited type 1 protein kinase interacting with the homeodomain (HIPK1) and weakening glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in vitro [11]. Experimental hyperexpression of miR-200 (in an animal model) led to beta cell apoptosis of the islets of Langerhans by inhibiting the expression of anti-apoptosis and stress resistance gene DNAJC3 (DnaJ homologue subfamily C member 3), crucial for the development of diabetes mellitus, and XIAP (X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein) gene, an inhibitor of apoptotic caspases [21].

MiR-204 downregulates the expression of glucagon-like peptide type 1 receptor (GLP1) on the surface of beta cells, thereby blocking GLP1-induced insulin release from beta cells by increasing their sensitivity to glucose [11]. MiR-375 has a mechanism similar to miR-7 that affects myotrophin expression that binds to free CAPZA1 and regulates its activity, preventing CAPZA1 from binding to the pointed end of F-actin [11].

MiR-802 reduces insulin expression, since it prevents the insulin-encoding gene promoter from binding to NEUROD1 transcription factor (neurogenic differentiation 1). This factor activates the transcription of genes containing a specific DNA sequence known as the E-box and regulates the expression of the insulin gene by affecting the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Inhibition of insulin secretion works in a similar way to miR-26a: it counteracts calcium influx by suppressing WNT5A receptors (protein Wnt-5a) that act in an autocrine/paracrine form and transmit signals through Ca²⁺/calmodulin-dependent type II protein kinase stimulating the activity of the high-voltage calcium channel for calcium influx [22].

Regulation of glucose metabolism

Mir-7a, miR-26a, miR-27, miR-29, miR-33b, miR-103, miR-107, miR-124, miR-130a, miR-130b, miR-143, miR-152, miR-155, miR-187, miR-200, miR-204, miR-336, miR-375, miR-378, miR-451-1, miR-466b, and miR-802 are known to promote gluconeogenesis and metabolism.

MiR-27, miR-29, and miR-451-1 inhibit gluconeogenesis in the liver by regulating functional activity of the gluconeogenesis pathway (glycerol kinase, GK) and transcription factor (FOXO1) [11]. MiR-33b directly inhibits the expression of two key gluconeogenesis genes encoding phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (PCK1) and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6PC); this suppresses gluconeogenesis [11]. MiR-466b directly inhibits the expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), a key gluconeogenetic enzyme [11]. The suppression mechanisms of glucose metabolism in other microRNAs were discussed previously [11][16-22].

Appetite regulation

By affecting various brain structures, as well as multiple signaling pathways described below, APs of the first and newer generations are able to affect appetite regulation and cause a binge-eating disorder associated with AIMetS [76][77].

The studies revealed that microRNAs are involved in the appetite regulation by targeting the neurons of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and neuropeptide Y (NPY) in the arquate nuclei of the hypothalamus. In particular, orexigenic microRNAs include miR-let7a, miR-7a, miR-9, miR-30E, miR-130, miR-141, miR-145, miR-200A, miR-218, miR-342, miR-383, miR-384-3P, miR-429, and miR-488.

MiR-7a is highly expressed in NPY/AgRP neurons that exert an orexigenic effect [28]. Overexpression of miR-200a in the hypothalamus is associated with impaired food intake control and compromised leptin/insulin signaling through changed IRS2 expression. MiR-141 and miR-429 have a similar orexigenic mechanism [25]. Starving leads to overexpression of miR-let7a, miR-9, miR-30e, miR-132, miR-145, and miR-218, which indicates the orexigenic effect of these microRNAs [27].

With a decreased leptin production, the expression levels of miR-383, miR-384-3p, and miR-488 increase, resulting in the inhibited matrix RNA of the POMC gene that encodes a key anorexigenic regulator of food intake [25]. MiR-342 is associated with the growing population and increased activation of NPY-orexigenic neurons, which leads to increased food consumption [26] with a risk of abdominal obesity.

Regulation of neuropeptide Y expression

Long-term intake of certain APs (for example, clozapine and risperidone) can lead to increased serum NPY and other AIMetS biomarkers [77][78].

MicroRNAs associated with an increased NPY expression have been identified. Thus, overexpression of miR-708 and miR-2137 in hypothalamic cell models increases the level of Npy mRNA expression through an indirect mechanism that does not involve direct binding to Npy 3'UTR [29].

Regulation of leptin sensitivity

Recently, active discussions concerned the influence of new AP generations on changing serum levels of the peptide hormone leptin (energy metabolism) and leptin sensitivity of adipocytes. By effecting cellular receptors in the arcuate and ventromedial nuclei of the hypothalamus, this hormone participates in appetite regulation, prevents hyperphagia and obesity. Recent studies have shown that changing leptin blood level can be considered as a promising AIMetS biomarker in SSD patients [77][79].

A negative correlation has been shown between increased miR-15a, miR-16, miR-33, miR-223, miR-363, and miR-532 and decreased plasma leptin [8]. In addition, overexpression of miR-200a, miR-200b, and miR-429 was detected in orexigenic hypothalamic neurons in knockout mice with primary leptin deficiency and primary leptin receptor deficiency (LepR). MiR-200a directly inhibits IRS2 and LepR, its primary targets. Inhibition of miR-200a in the hypothalamus increases the mRNA expression of LEPR and IRS2 by increasing the sensitivity of orexigenic hypothalamic neurons to leptin and insulin [28].

Regulation of orexin expression

AIMetS in SSD patients may be directly related to the effect of APs on molecules involved in the regulation of systemic metabolism, in particular orexin, a neuropeptide synthesised by hypothalamic neurons [80]. Some microRNAs inhibit orexin expression, which is of clinical interest, since not only is this neuropeptide involved in the regulation of the sleep-wake cycle and autonomic functions, but it also regulates eating behavior.

Notably, miR-137, miR-637, miR-654, and miR-665 inhibit HCRT mRNAs in the hypothalamic neurons [19]. Moreover, researchers note that miR-137 is genetically associated both with an increased AIMetS risk in patients with mental disorders and directly with the risk of developing mental disorders (particularly schizophrenia) [32].

Regulating thyroid hormone expression

It is known that long-term use of APs is associated with changed expression of thyroid hormones and impaired thyroid function. At the same time, most of the previous studies demonstrated an AP-induced increase in thyroid-stimulating hormone expression [81]. A reduced level of these hormones correlates with increased blood concentrations of total cholesterol, LDL and triglycerides. In this case, pathogenetic progression of dyslipidemia associated with secondary hypothyroidism may be associated with decreased serum concentrations of thyroid hormones and increased serum concentrations of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Thus, AP-induced hypothyroidism can cause dyslipidemia and related metabolic disorders, including AIMetS [82].

Several microRNAs (miR-21, miR-146, miR-214) that induce the expression of thyroid hormones have been identified. MicroRNAs control the expression of thyroid hormones by regulating enzymes of the deiodinase family. Type 1 (DIO1) and type 2 (DIO2) deiodinases catalyze T4 to T3 conversion in target tissues, thus increasing the intracellular level of the active hormone. Type 3 deiodinase (DIO3) causes hormone inactivation, since it converts T4 (thyroxine) and T3 (triiodothyronine) into inactive metabolites (rT3 is a biologically inactive isomer of the thyroid hormone T3; and T2, known as 3,5-T2 — Janus-faced thyroid hormone metabolite) by deiodation along the inner ring [34]. In addition, some microRNAs (miR-27, miR-155, miR-181, miR-200a, miR-221, miR-224, miR-246, miR-383, miR-425) reduce the expression of thyroid hormones [34]. At the same time, miR-27, miR-155, miR-181, miR-200a, miR-221, miR-246, and miR-425 reduce TRß expression, which, together with regulation of DIO1, leads to local hypothyroidism and decreased thyroid hormone signaling. Overexpression of miR-224 and miR-383 represses DIO1 mRNA, which leads to decreased thyroid hormone production [34].

Regulating parathyroid hormone expression

Metabolic disorders associated with vitamin D deficiency are synergistic with other pathways, contributing to weight gain induced by APs. Although the direct catabolic effect of APs on vitamin D molecule has not been demonstrated, APs can reduce blood parathyroid hormone (PTH) due to the buildup of adipose tissue and follicular structures, decreased functional activity of the dark chief cells and enhance the function of oxyphil cells in the parathyroid gland, hinder vitamin D metabolism and reduce its level [83]. Overexpression of miR-24 inhibits PTH production by binding CDKN1B/p27, CDKN2A/p16, TGFβ1, and CASP8 transcripts involved in the development of hyperparathyroidism [35].

In turn, miR-27b inhibits the expression of VDR (vitamin D receptor) gene encoding the nuclear vitamin D receptor, thereby reducing cell sensitivity to vitamin D, causing secondary hyperparathyroidism [35].

Prospects of using microRNAs as AIMetS biomarkers

Proceeding to personalised psychiatry reflects modern approaches to the individual safety assessment and risk of AP adverse reactions associated with psychopharmacotherapy [84][85]. The study of AP-induced changes in microRNA expression is possible in various tissues (brain, peripheral tissues). However, microRNAs circulating in the peripheral blood (plasma, exosomes, and mononuclear cells) are of greatest clinical interest due to highly available biological samples. For example, risperidone and aripiprazole are known to inhibit the expression of circulating miR-130b and miR-193a-3p [86] in blood plasma, while olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and risperidone inhibit the expression of miR-30e, miR-132, miR-195, and miR-432 [87]; risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, aripiprazole, and ziprasidone increase the expression of miR-30a-5p in peripheral blood mononuclears [88]; olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and risperidone decrease the expression of miR-21 [89], while risperidone increases the expression of miR-132, miR-664*, and miR-1271 [90].

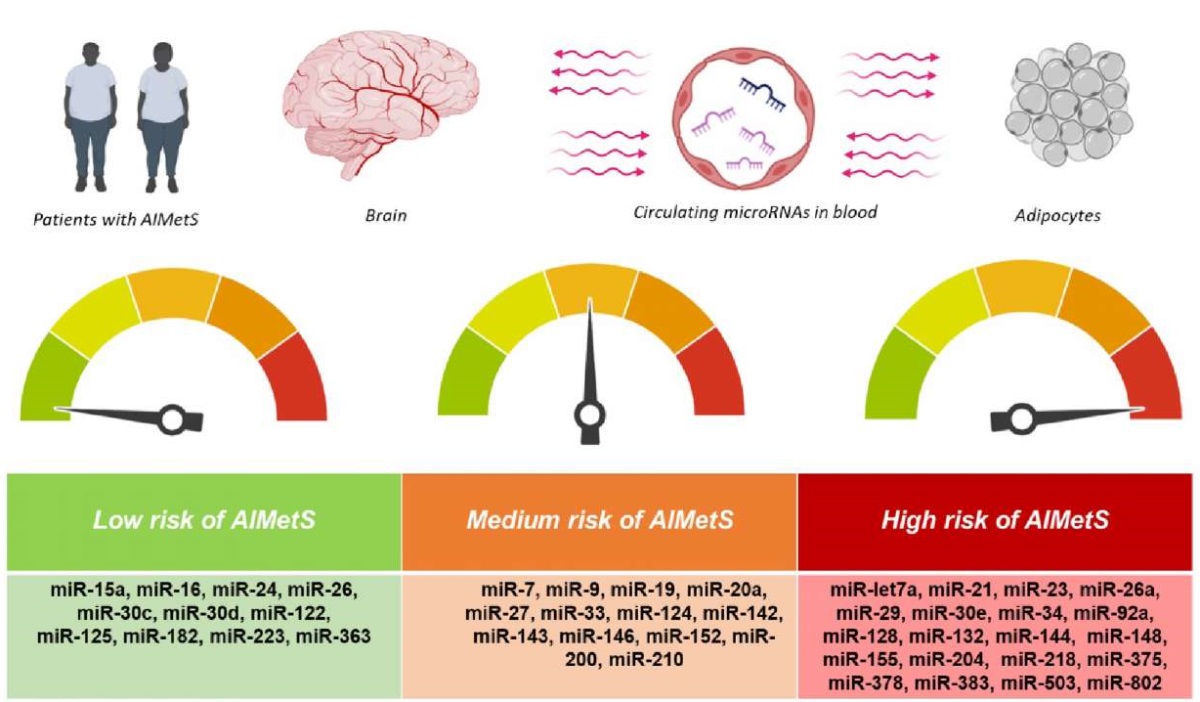

The analysed results of 34 studies (9 clinical and 25 preclinical) over 2014-2024 reflected the role of microRNAs in the key links of MetS and AIMetS pathogenesis. Studies in psychiatry patients (with mental disorders) with MetS in general and AIMetS in particular are still isolated and performed on small samples, which does not allow us to summarize the results and translate them into clinical practice. However, this review demonstrates the potential role of circulating microRNAs as prognostic or predictive epigenetic AIMetS biomarkers, especially microRNAs involved in several links of AIMetS pathogenesis. This made it possible to gradate microRNAs by risk of AIMetS: low risk for microRNAs with purely protective properties towards two or more links in the AIMetS pathogenesis; average risk for microRNAs with predictive properties towards one link of pathogenesis, but protective properties towards another link; high risk for microRNA predictors towards two or more links in AIMetS pathogenesis (Figure 1).

The figure was prepared by the authors

Figure 1. Circulating microRNA classification based on the risk of antipsychotic-induced metabolic syndrome (AIMetS)

A continued study of these microRNAs would be essential for the subsequent planning of translational clinical trials that ensure adaptation and application of the results in real clinical practice of a psychiatrist. Given that circulating microRNAs are stable molecules during sample preparation and repeated freeze-thaw cycles, the study of their blood levels is promising due to the expected highly repeatable results obtained in different AIMetS patients.

At the same time, data of certain analysed studies are contradictory. Overexpression of proinflammatory [9] microRNA (miR-let7a) was associated with insulin resistance [11]. Moreover, this microRNA had orexigenic properties associated with increased sensitivity to leptin [27]. However, its paralogue miR-let7b inhibited NPY expression, which led to appetite suppression and a reduced risk of abdominal obesity [29]. MiR-7 induced lipid metabolism [11] and prevented systemic inflammation [9]; however, it suppressed carbohydrate metabolism by reducing insulin expression [11] and had orexigenic effect [28]. The anti-inflammatory miR-9 [9] also showed orexigenic properties through increased sensitivity to leptin [27]. A systemic inflammation inhibitor, miR-20a [9] can be an adipogenesis inducer [10], while its two paralogues (miR-26 and miR-26a) exert an essentially different effect on glucose metabolism. MiR-26 activates insulin expression and, as a result, enhances carbohydrate metabolism by inhibiting insulin transcription repressors [23]; still, its paralogue (miR-26a) inhibits the SNARE-dependent release of insulin into the systemic circulation [19].

Studies on the role of miR-27 and its paralogues in MetS and AIMetS pathogenesis are ambivalent. For example, miR-27a inhibited the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway [6] and induced systemic inflammation [9], as well as glycogen accumulation in skeletal muscles and myocardium [11]. However, miR-27a suppressed adipocyte differentiation [10] and regulated lipid metabolism in the liver, preventing NAFLD together with miR-27b [11]. MiR-27 inhibited adipogenesis by activating Wnt pathway in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes [10]; at the same time, it reduced glucose production by the liver affecting enzymes of the gluconeogenic pathway [11] and promoted hypothyroidism [34].

Some researchers did not study paralogues; instead, they assessed the role of individual links in MetS and AIMetS pathogenesis as a whole. In our opinion, this causes confusion and impairs the understanding of the obtained results. For example, miR-33 microRNAs had an impact on MetS pathogenesis [8][11][28]. In general, the overexpression of this microRNA family caused abdominal obesity and insulin resistance. MiR-33a and miR-33b paralogues co-ordinatively inhibited reverse cholesterol transport from the periphery back to the liver, fatty acid oxidation enzymes, and inhibit cholesterol excretion from the body [11]. The underexpression of miR-33a/b had atheroprotective effects, such as regulating functional polarisation of macrophages and increased cholesterol transport from macrophages to plasma, liver and faeces, thus preventing the formation of foam cells and atherosclerosis [8]. The miR-33 family reduced insulin sensitivity, resulting in insulin resistance. MiR-33 regulated glucose metabolism by suppressing glycogenolytic enzymes, which caused glycogen accumulation in the liver. Studies also demonstrated that the miR-33 and miR-33b in particular directly interfered with the expression of gluconeogenesis enzymes [11]. Additionally, it was found that miR-33 overexpression (without specifying the paralogues) suppressed appetite, reducing the activity of AgRP neurons in the hypothalamus [24]; however, it also reduced sensitivity to leptin [28].

MiR-142 ambiguously affected the risk of MetS and AIMetS. Its anti-inflammatory effect was associated with the inhibited synthesis of pro-inflammatory molecules [9], and its pro-oxidant effect was caused by a decreased transcription of the Nrf2 pathway [6]. Anti-inflammatory miR-143 [9] reduced NPY expression [29]; however, it was associated with increased adipogenic differentiation in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes, abdominal obesity [10], and insulin resistance [11].

The prooxidant miR-146 [7] exerted an anti-inflammatory effect [9]. Its paralogues, miR-146a and miR-146b, exerted fundamentally different effects on adipogenesis. MiR-146a inhibited adipogenesis, while miR-146b promoted adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes [10]. MiR-146 increased thyroid hormones [34], while its paralogue miR-146b induced PTH expression [35].

MiR-152 protected cells from oxidative stress [6]; however, it also reduced insulin synthesis and secretion [20]. Antioxidant [6] and anti-inflammatory [9] miR-210 induced adipogenesis and thus is a biomarker of abdominal obesity [10].

The differences in the presented results are possibly due to the fact that the analysed fundamental (mainly) and clinical studies had a variable design, as well as the fact that they did not consider modifiable and unmodifiable MetS and AIMetS risk factors, such as low physical inactivity, alcohol consumption, and genetic predisposition.

CONCLUSION

This review demonstrates that the sensitivity and specificity of AIMetS epigenetic biomarkers can vary widely depending on their effect (predictive or protective) on one or more main pathogenic components of a common psychopharmacotherapeutic ADR. This may include oxidative stress; systemic inflammation; adipogenesis control and abdominal obesity onset; lipid metabolism; HDL and LDL cholesterol homeostasis; atherogenesis; liver steatosis, as well as insulin sensitivity control and its expression; glucose metabolism; appetite control; expression of neuropeptide Y, orexin, thyroid hormones, parathyroid hormone, and sensitivity to leptin. The most well-studied microRNAs are predictive biomarkers of oxidative stress (miR-1, miR-21, miR-23b, miR-27a, miR-28, miR-29, miR-34a, miR-92a, miR-93, miR-101, miR-106b, miR-128, miR-129, miR-140, miR-142, miR-144, miR-146, miR-148, miR-153, miR-155, miR-181c, miR-193b, miR-320, miR-365, miR-375, miR-383, miR-495, miR-503, miR-802) and systemic inflammation (miR-21, miR-23a, miR-27a, miR-29a, miR-34a, miR-34c, miR-92a, miR-132, miR-138, miR-155, miR-200, and miR-let7a) in patients with the high MetS and AIMetS risk. Promising predictive epigenetic AIMetS biomarkers that arouse great scientific and clinical interest are microRNAs that influence the expression of neuropeptides and sensitivity to these neuropeptides, including NPY (miR-let7b, miR-29b, miR-33, miR-140- miR-143, miR-503), leptin (miR-let7a, miR-9, miR-30e, miR-132, miR-145, miR-218, miR-342), and orexin (miR-137, miR-637, miR-654, miR-665).

Future research may include not solely microRNA predictive role in the pathogenesis of the main AIMetS components, but also integrated development of circulating microRNA signatures that are most sensitive and specific in patients with high AIMetS risk.

Developing new epigenetic biomarker panels of this common ADR caused by the first and newer AP generations will contribute to improved pharmacotherapeutic safety in psychiatric disorders. However, in order to implement the results of global preclinical and clinical studies into clinical practice, further Russian studies are warranted to clarify sensitivity and specificity data of circulating microRNAs as AIMetS biomarkers.

Authors’ contributions. All the authors confirm that they meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship. The most significant contributions were as follows. Natalia А. Shnayder drafted the manuscript and revised it based on the peer-review results. Regina F. Nasyrova developed the general concept of the study, managed the project, and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication. Nikolai A. Pekarets worked with databases and drafted the manuscript. Violetta V. Grechkina worked with databases and prepared illustrations. Marina M. Petrova designed the study and edited the manuscript.

Вклад авторов. Все авторы подтверждают соответствие своего авторства критериям ICMJE. Наибольший вклад распределен следующим образом: Н.А. Шнайдер — написание текста рукописи и ее доработка по результатам рецензирования; Р.Ф. Насырова — общая концепция, руководство проектом, утверждение окончательной версии рукописи для публикации; Н.А. Пекарец — работа с базами данных, написание текста рукописи; В.В. Гречкина — работа с базами данных, подготовка графических материалов; М.М. Петрова — дизайн исследования, редактирование текста рукописи.

References

1. Correll CU, Solmi M, Croatto G, et al. Mortality in people with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of relative risk and aggravating or attenuating factors. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):248–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20994

2. Peritogiannis V, Ninou A, Samakouri M. Mortality in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: Recent advances in understanding and management. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(12):2366. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122366

3. De Hert M, Detraux J, van Winkel R, Yu W, Correll C. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects associated with antipsychotic drugs. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(2):114–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2011.156

4. De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Cohen D, Asai I, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014.x

5. Khasanova AK, Dobrodeeva VS, Shnayder NA, Petrova MM, Pronina EA, Bochanova EN, et al. Blood and urinary biomarkers of antipsychotic-induced metabolic syndrome. Metabolites. 2022;12(8):726. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo12080726

6. Saha S. Role of microRNA in oxidative stress. Stresses. 2024;4(2):269–81. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses4020016

7. Włodarski A, Strycharz J, Wróblewski A, Kasznicki J, Drzewoski J, Śliwińska A. The role of microRNAs in metabolic syndrome-related oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(18):6902. https://www.doi.org/10.3390/ijms21186902

8. Carvalho GB, Brandão-Lima PN, Payolla TB, Lucena SEF, Sarti FM, Fisberg RM, Rogero MM. Circulating miRNAs are associated with low-grade systemic inflammation and leptin levels in older adults. Inflammation. 2023;46(6):2132–46. https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s10753-023-01867-6

9. Das K, Rao LVM. The role of microRNAs in inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(24):15479. https://www.doi.org/10.3390/ijms232415479

10. Engin AB, Engin A. Adipogenesis-related microRNAs in obesity. ExRNA. 2022;4:16. https://www.doi.org/10.21037/exrna-22-4

11. Agbu P, Carthew RW. MicroRNA-mediated regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(6):425–38. https://www.doi.org/10.1038/s41580-021-00354-w

12. Dong M, Ye Y, Chen Z, Xiao T, Liu W, Hu F. MicroRNA 182 is a novel negative regulator of adipogenesis by targeting CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28(8):1467–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22863

13. Wagschal A, Najafi-Shoushtari SH, Wang L, Goedeke L, Sinha S, deLemos AS, et al. Genome-wide identification of microRNAs regulating cholesterol and triglyceride homeostasis. Nat Med. 2015;21(11):1290–7. https://www.doi.org/10.1038/nm.3980

14. Cheng J, Cheng A, Clifford BL, Wu X, Hedin U, Maegdefessel L, et al. MicroRNA-144 silencing protects against atherosclerosis in male, but not female mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(2):412–25. https://www.doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313633

15. Irani S, Iqbal J, Antoni WJ, Ijaz L, Hussain MM. MicroRNA-30c reduces plasma cholesterol in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemic and type 2 diabetic mouse models. J Lipid Res. 2018;59(1):144–54. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M081299

16. Trajkovski M, Hausser J, Soutschek J, Bhat B, Akin A, Zavolan M, et al. MicroRNAs 103 and 107 regulate insulin sensitivity. Nature. 2011;474(7353):649–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10112

17. Liu W, Cao H, Ye C, Chang C, Lu M, Jing Y, et al. Hepatic miR-378 targets p110α and controls glucose and lipid homeostasis by modulating hepatic insulin signalling. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5684. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6684

18. Kornfeld JW, Baitzel C, Könner AC, Nicholls HT, Vogt MC, Herrmanns K, et al. Obesity-induced overexpression of miR-802 impairs glucose metabolism through silencing of Hnf1b. Nature. 2013;494(7435):111–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11793

19. Xu H, Du X, Xu J, Zhang Y, Tian Y, Liu G, et al. Pancreatic β cell microRNA-26a alleviates type 2 diabetes by improving peripheral insulin sensitivity and preserving β cell function. PLoS Biol. 2020;18(2):e3000603. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000603

20. Ofori JK, Salunkhe VA, Bagge A, Vishnu N, Nagao M, Mulder H, et al. Elevated miR-130a/miR130b/miR-152 expression reduces intracellular ATP levels in the pancreatic beta cell. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44986. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44986

21. Belgardt BF, Ahmed K, Spranger M, Latreille M, Denzler R, Kondratiuk N, et al. The microRNA-200 family regulates pancreatic beta cell survival in type 2 diabetes. Nat Med. 2015;21(6):619–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3862

22. Zhang F, Ma D, Zhao W, Wang D, Liu T, Liu Y, et al. Obesity-induced overexpression of miR-802 impairs insulin transcription and secretion. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1822. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15529-w

23. Melkman-Zehavi T, Oren R, Kredo-Russo S, Shapira T, Mandelbaum AD, Rivkin N, et al. miRNAs control insulin content in pancreatic β-cells via downregulation of transcriptional repressors. EMBO J. 2011;30(5):835–45. https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2010.361

24. Price NL, Fernández-Tussy P, Varela L, Cardelo MP, Shanabrough M, Aryal B, et al. microRNA-33 controls hunger signaling in hypothalamic AgRP neurons. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):2131. https://www.doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46427-0

25. Taouis M. MicroRNAs in the hypothalamus. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;30(5):641–51. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2016.11.006

26. Zhang D, Yamaguchi S, Zhang X, Yang B, Kurooka N, Sugawara R, et al. Upregulation of mir342 in diet-induced obesity mouse and the hypothalamic appetite control. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:727915. https://www.doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.727915

27. Sangiao-Alvarellos S, Pena-Bello L, Manfredi-Lozano M, Tena-Sempere M, Cordido F. Perturbation of hypothalamic microRNA expression patterns in male rats after metabolic distress: Impact of obesity and conditions of negative energy balance. Endocrinology. 2014;155(5):1838–50. https://www.doi.org/10.1210/en.2013-1770

28. Derghal A, Djelloul M, Azzarelli M, Degonon S, Tourniaire F, Landrier JF, et al. MicroRNAs are involved in the hypothalamic leptin sensitivity. Epigenetics. 2018;13(10–11):1127–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592294.2018.1543507

29. Mak KWY, He W, Loganathan N, Belsham DD. Bisphenol A Alters the levels of miRNAs that directly and/or indirectly target neuropeptide Y in murine hypothalamic neurons. Genes (Basel). 2023;14(9):1773. https://www.doi.org/10.3390/genes14091773

30. Dobrodeeva VS, Abdyrahmanova AK, Nasyrova RF. Personalized approach to antipsychotic-induced weight gain prognosis. Personalized Psychiatry and Neurology. 2021;1(1):3–10. https://doi.org/10.52667/2712-9179-2021-1-1-3-10

31. Holm A, Possovre ML, Bandarabadi M, Moseholm KF, Justinussen JL, Bozic I, et al. The evolutionarily conserved miRNA-137 targets the neuropeptide hypocretin/orexin and modulates the wake to sleep ratio. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119(17):e2112225119. https://www.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2112225119

32. Siegert S, Seo J, Kwon EJ, Rudenko A, Cho S, Wang W, et al. The schizophrenia risk gene product miR-137 alters presynaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(7):1008–16. https://www.doi.org/10.1038/nn.4023

33. Azhar S, Dong D, Shen WJ, Hu Z, Kraemer FB. The role of miRNAs in regulating adrenal and gonadal steroidogenesis. J Mol Endocrinol. 2020;64(1):R21–R43. https://www.doi.org/10.1530/JME-19-0105

34. Aranda A. MicroRNAs and thyroid hormone action. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2021;525:111175. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2021.111175

35. Vaira V, Verdelli C, Forno I, Corbetta S. MicroRNAs in parathyroid physiopathology. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;456:9–15. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2016.10.035

36. Shnayder NA, Nasyrova RF, Pekarets NA, Grechkina VV, Petrova MM. Circulating microRNAs are promising biomarkers for assessing the risk of antipsychotic-induced metabolic syndrome (review): Part 1. Safety and Risk of Pharmacotherapy. 2025. https://doi.org/10.30895/2312-7821-2025-478

37. Dietrich-Muszalska A, Kolodziejczyk-Czepas J, Nowak P. Comparative study of the effects of atypical antipsychotic drugs on plasma and urine biomarkers of oxidative stress in schizophrenic patients. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:555–65. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S283395

38. Tsai MC, Liou CW, Lin TK, Lin IM, Huang TL. Changes in oxidative stress markers in patients with schizophrenia: The effect of antipsychotic drugs. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209(3):284–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.01.023

39. Bhandari R, Kaur J, Kaur S, Kuhad A. The Nrf2 pathway in psychiatric disorders: Pathophysiological role and potential targeting. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2021;25(2):115–39. https://www.doi.org/10.1080/14728222.2021.1887141

40. Fang X, Yu L, Wang D, Chen Y, Wang Y, Wu Z, et al. Association between SIRT1, cytokines, and metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia patients with olanzapine or clozapine monotherapy. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:602121. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.602121

41. Tkachev VO, Menshchikova EB, Zenkov NK. Mechanism of the Nrf2/Keap1/ARE signaling system. Biochemistry (Moscow). 2011;76(4):407–22 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.1134/s0006297911040031

42. Zhang H, Dai S, Yang Y, Wei J, Li X, Luo P, Jiang X. Role of sirtuin 3 in degenerative diseases of the central nervous system. Biomolecules. 2024;13(5):735. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13050735

43. Yang W, Nagasawa K, Munch C, Xu Y, Satterstrom K, Jeong S, et al. Mitochondrial sirtuin network reveals dynamic Sirt3-dependent deacetylation in response to membrane depolarization. Cell. 2016;167(4):985–1000.e21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.016

44. Lee BJ, Marchionni L, Andrews CE, Norris AL, Nucifora LG, Wu YC, et al. Analysis of differential gene expression mediated by clozapine in human postmortem brains. Schizophr Res. 2017;185:58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.12.017

45. Sommerfeld-Klatta K, Jiers W, Rzepczyk S, Nowicki F, Łukasik-Głębocka M, Świderski P, et al. The effect of neuropsychiatric drugs on the oxidation-reduction balance in therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(13):7304. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25137304

46. Nasyrova RF, Moskaleva PV, Vaiman EE, Shnayder NA, Blatt NL, Rizvanov AA. Genetic factors of nitric oxide’s system in psychoneurologic disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(5):1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms2105160

47. Patel S, Keating BA, Dale RC. Anti-inflammatory properties of commonly used psychiatric drugs. Front Neurosci. 2023;16:1039379. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.1039379

48. Al-Amin MM, Nasir Uddin MM, Mahmud Reza H. Effects of antipsychotics on the inflammatory response system of patients with schizophrenia in peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2013;11(3):144–51. https://doi.org/10.9758/cpn.2013.11.3.144

49. Marcinowicz P, Więdłocha M, Zborowska N, Dębowska W, Podwalski P, Misiak B, et al. A meta-analysis of the influence of antipsychotics on cytokines levels in first episode psychosis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(11):2488. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10112488

50. Patlola SR, Donohoe G, McKernan DP. Anti-inflammatory effects of 2nd generation antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;160:126–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.01.042

51. Cohen T, Sundaresh S, Levine F. Antipsychotics activate the TGFβ pathway effector SMAD3. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(3):347–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2011.186

52. Prestwood TR, Asgariroozbehani R, Wu S, Agarwal SM, Logan RW, Ballon JS, et al. Roles of inflammation in intrinsic pathophysiology and antipsychotic drug-induced metabolic disturbances of schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res. 2021;402:113101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2020.113101

53. Melbourne JK, Pang Y, Park MR, Sudhalkar N, Rosen C, Sharma RP. Treatment with the antipsychotic risperidone is associated with increased M1-like JAK-STAT1 signature gene expression in PBMCs from participants with psychosis and THP-1 monocytes and macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;79:106093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2019.106093

54. Cheng L, Xia F, Li Z, Shen C, Yang Z, Hou H, et al. Structure, function and drug discovery of GPCR signaling. Mol Biomed. 2023;4(1):46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43556-023-00156-w

55. Chen CY, Liu HY, Hsueh YP. TLR3 downregulates expression of schizophrenia gene Disc1 via MYD88 to control neuronal morphology. EMBO Rep. 2017;18(1):169–83. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201642586

56. Kositsyn YM, de Abreu MS, Kolesnikova TO, Lagunin AA, Poroikov VV, Harutyunyan HS, et al. Towards novel potential molecular targets for antidepressant and antipsychotic pharmacotherapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(11):9482. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119482

57. Bahmad HF, Daouk R, Azar J, Sapudom J, Teo JCM, Abou-Kheir W, et al. Modeling adipogenesis: Current and future perspective. Cells. 2020;9(10):2326. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9102326

58. Ghesmati Z, Rashid M, Fayezi S, Gieseler F, Alizadeh E, Darabi M. An update on the secretory functions of brown, white, and beige adipose tissue: Towards therapeutic applications. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2024;25(2):279–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-023-09850-0

59. Li Y, Zhao X, Feng X, Liu X, Deng C, Hu CH. Berberine alleviates olanzapine-induced adipogenesis via the AMPKα-SREBP pathway in 3T3-L1 Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(11):1865. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17111865

60. Chen CC, Hsu LW, Huang KT, Goto S, Chen CL, Nakano T. Overexpression of Insig-2 inhibits atypical antipsychotic-induced adipogenic differentiation and lipid biosynthesis in adipose-derived stem cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10901. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11323-9

61. Fehsel K, Bouvier ML. Sex-specific effects of long-term antipsychotic drug treatment on adipocyte tissue and the crosstalk to liver and brain in rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(4):2188. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25042188

62. Ma J, Zheng Y, Sun F, Fan Y, Fan Y, Su X, et al. Research progress in the correlation between SREBP/PCSK9 pathway and lipid metabolism disorders induced by antipsychotics. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2023;48(10):1529–38. https://doi.org/10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2023.230029

63. Vantaggiato C, Panzeri E, Citterio A, Orso G, Pozzi M. Antipsychotics promote metabolic disorders disrupting cellular lipid metabolism and trafficking. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2019;30(3):189–210. https://doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.tem.2019.01.003

64. Delacrétaz A, Vandenberghe F, Glatard A, Dubath C, Levier A, Gholam-Rezaee M, et al. Lipid disturbances in adolescents treated with second-generation antipsychotics: Clinical determinants of plasma lipid worsening and new-onset hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(3):18m12414. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.18m12414

65. O’Donnell C, Demler TL, Trigoboff E, Lee C. The impact of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels and risk of movement disorders in patients taking antipsychotics. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2024;21(4–6):27–30. PMCID: PMC11208005

66. Richards-Belle A, Austin-Zimmerman I, Wang B, Zartaloudi E, Cotic M, Gracie C, et al. Associations of antidepressants and antipsychotics with lipid parameters: Do CYP2C19/CYP2D6 genes play a role? A UK population-based study. J Psychopharmacol. 2023;37(4):396–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/02698811231152748

67. Chen CH, Leu SJ, Hsu CP, Pan CC, Shyue SK, Lee TS. Atypical antipsychotic drugs deregulate the cholesterol metabolism of macrophage-foam cells by activating NOX-ROS-PPARγ-CD36 signaling pathway. Metabolism. 2021;123:154847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154847

68. Gangopadhyay A, Ibrahim R, Theberge K, May M, Houseknecht KL. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and mental illness: Mechanisms linking mood, metabolism and medicines. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:1042442. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.1042442

69. Chen J, Huang XF, Shao R, Chen C, Deng C. Molecular mechanisms of antipsychotic drug-induced diabetes. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:643. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2017.00643

70. Weeks KR, Dwyer DS, Aamodt EJ. Antipsychotic drugs activate the C. elegans Akt pathway via the DAF-2 insulin/IGF-1 receptor. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2010;1(6):463–73. https://doi.org/10.1021/cn100010p

71. Kowalchuk C, Kanagasundaram P, Belsham DD, Hahn MK. Antipsychotics differentially regulate insulin, energy sensing, and inflammation pathways in hypothalamic rat neurons. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;104:42–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.01.029

72. Li YZ, Di Cristofano A, Woo M. Metabolic role of PTEN in insulin signaling and resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2020;10(8):a036137. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a036137

73. Ramasubbu K, Devi Rajeswari V. Impairment of insulin signaling pathway PI3K/Akt/mTOR and insulin resistance induced AGEs on diabetes mellitus and neurodegenerative diseases: A perspective review. Mol Cell Biochem. 2023;478(6):1307–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-022-04587-x

74. Zhou W, Sun J, Huai C, Liu Y, Chen L, Yi Z, et al. Multi-omics analysis identifies rare variation in leptin/PPAR gene sets and hypermethylation of ABCG1 contribute to antipsychotics-induced metabolic syndromes. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(12):5195–205. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01759-5

75. Nwosu BU, Meltzer B, Maranda L, Ciccarelli C, Reynolds D, Curtis L, et al. A potential role for adjunctive vitamin D therapy in the management of weight gain and metabolic side effects of second-generation antipsychotics. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2011;24(9–10):619–26. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem.2011.300

76. Mukherjee S, Skrede S, Milbank E, Andriantsitohaina R, López M, Fernø J. Understanding the effects of antipsychotics on appetite control. Front Nutr. 2022;8:815456. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.815456

77. Dobrodeeva VS, Shnayder NA, Mironov KO, Nasyrova RF. Pharmacogenetic markers of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: Leptin and neuroepeptide Y. V.M. Bekhterev Review of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology. 2021;55(1):3–10 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.31363/2313-7053-2021-1-3-10

78. Klemettilä JP, Kampman O, Solismaa A, Lyytikäinen LP, Seppälä N, Viikki M, et al. Association study of arcuate nucleus neuropeptide Y neuron receptor gene variation and serum Npy levels in clozapine treated patients with schizophrenia. European Psychiatry. 2017;40:13–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.07.004

79. Zhang Y, Li X, Yao X, Yang Y, Ning X, Zhao T, et al. Do leptin play a role in metabolism-related psychopathological symptoms? Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:710498. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.710498

80. Chen PY, Chang CK, Chen CH, Fang SC, Mondelli V, Chiu CC, et al. Orexin-a elevation in antipsychotic-treated compared to drug-free patients with schizophrenia: A medication effect independent of metabolic syndrome. J Formos Med Assoc. 2022;121(11):2172–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2022.03.008

81. Burghardt KJ, Mando W, Seyoum B, Yi Z, Burghardt PR. The effect of antipsychotic treatment on hormonal, inflammatory, and metabolic biomarkers in healthy volunteers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2022;42(6):504–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.2689

82. Su X, Chen X, Peng H, Song J, Wang B, Wu X. Novel insights into the pathological development of dyslipidemia in patients with hypothyroidism. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2022;22(3):326–39. https://doi.org/10.17305/bjbms.2021.6606

83. Nwosu BU, Meltzer B, Maranda L, Ciccarelli C, Reynolds D, Curtis L, et al. A potential role for adjunctive vitamin D therapy in the management of weight gain and metabolic side effects of second-generation antipsychotics. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2011;24(9–10):619–26. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem.2011.300

84. Neznanov NG. A paradigm shift to treat psychoneurological disorders. Personalized Psychiatry and Neurology. 2021;1(1):1–2.

85. Ashurov ZS. The evolution of personalized psychiatry. Personalized Psychiatry and Neurology. 2023;3(2):1–2.

86. Wei H, Yuan Y, Liu S, Wang C, Yang F, Lu Z, et al. Detection of circulating miRNA levels in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(11):1141–7. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14030273

87. Liu S, Zhang F, Shugart YY, Yang L, Li X, Liu Z, et al. MiR143-3p-mediated NRG-1-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to olanzapine resistance in refractory schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;92(5):419–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.03.012

88. Liu S, Zhang F, Shugart YY, Yang L, Li X, Liu Z, et al. The early growth response protein 1-miR-30a-5p-neurogenic differentiation factor 1 axis as a novel biomarker for schizophrenia diagnosis and treatment monitoring. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(1):e998. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.268

89. Chen SD, Sun XY, Niu W, Kong LM, He MJ, Fan HM, et al. A preliminary analysis of microRNA-21 expression alteration after antipsychotic treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2016;244:324–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.087

90. Yu HC, Wu J, Zhang HX, Zhang GL, Sui J, Tong WW, et al. Alterations of miR-132 are novel diagnostic biomarkers in peripheral blood of schizophrenia patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2015;63:23–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.05.007

About the Authors

N. A. ShnayderRussian Federation

Natalia А. Shnayder - Dr. Sci. (Med.), Professor.

3 Bekhterev St., St Petersburg 192019; 1 Partisan Zheleznyak St., Krasnoyarsk 660022

R. F. Nasyrova

Russian Federation

Regina F. Nasyrova - Dr. Sci. (Med.)

3 Bekhterev St., St Petersburg 192019; 92 Lenin Ave, Tula 300012

N. A. Pekarets

Russian Federation

Nikolai A. Pekarets

3 Bekhterev St., St Petersburg 192019

V. V. Grechkina

Russian Federation

Violetta V. Grechkina

3 Bekhterev St., St Petersburg 192019

M. M. Petrova

Russian Federation

Marina M. Petrova - Dr. Sci. (Med.), Professor.

1 Partisan Zheleznyak St., Krasnoyarsk 660022

Supplementary files

Review

For citations:

Shnayder N.A., Nasyrova R.F., Pekarets N.A., Grechkina V.V., Petrova M.M. Circulating MicroRNAs Are Promising Biomarkers for Assessing the Risk of Antipsychotic-Induced Metabolic Syndrome (Review): Part 2. Safety and Risk of Pharmacotherapy. 2025;13(4):394-410. https://doi.org/10.30895/2312-7821-2025-499

JATS XML